Imagine being torn away from your friends and family and sentenced to a life of drudgery in a land so far away, you might as well have been thrown into the pit of Hell itself. Now imagine that you had one chance, one insanely long shot, to bust loose. Get caught, and you’d be jailed for life, if not just killed outright. Imagine then that your hopes of freedom hinge on the efforts of a rag-tag bunch of Irish revolutionaries and an American whaling captain turned hero – as unlikely a collection of conspirators as there ever was.

That’s a lot of imagining. Fortunately, history has done the heavy lifting for you. It all really happened here in Western Australia in 1876, and it’s remembered as The Catalpa Escape.

There’s a good chance that your mental picture of a transported convict is some poor cockney bastard who got pinged for stealing a heel of moldy bread to feed his starveling octuplets. There’s a good chance you’d imagine him being promptly sentenced to a life of misery carving some measure of civilisation out of the unforgiving Aussie outback half a planet away, toiling until he dropped dead of exhaustion or something poisonous got around to biting him. But the truth is that all kinds of folks got hurled into the Southern Hemisphere by the British Crown, some of them more rowdy than others. Take the Fenians, for example: bold Irish rebels in the classical style, sworn to liberate their homeland from English oppression, and banged up Down Under for their trouble.

In the 1870s only a few Fenians, were still doing it tough in Fremantle Prison, and were frankly getting quite sick of the whole mess. One of these men, James Wilson, managed to smuggle a letter out of the prison pleading for help. Wilson’s letter traversed the globe, reaching the leadership of the Clan na Gael, a militant Irish revolutionary group (as if there’s any other kind). The clan resolved to spring Wilson and his comrades from their limestone prison using guile rather than violence.

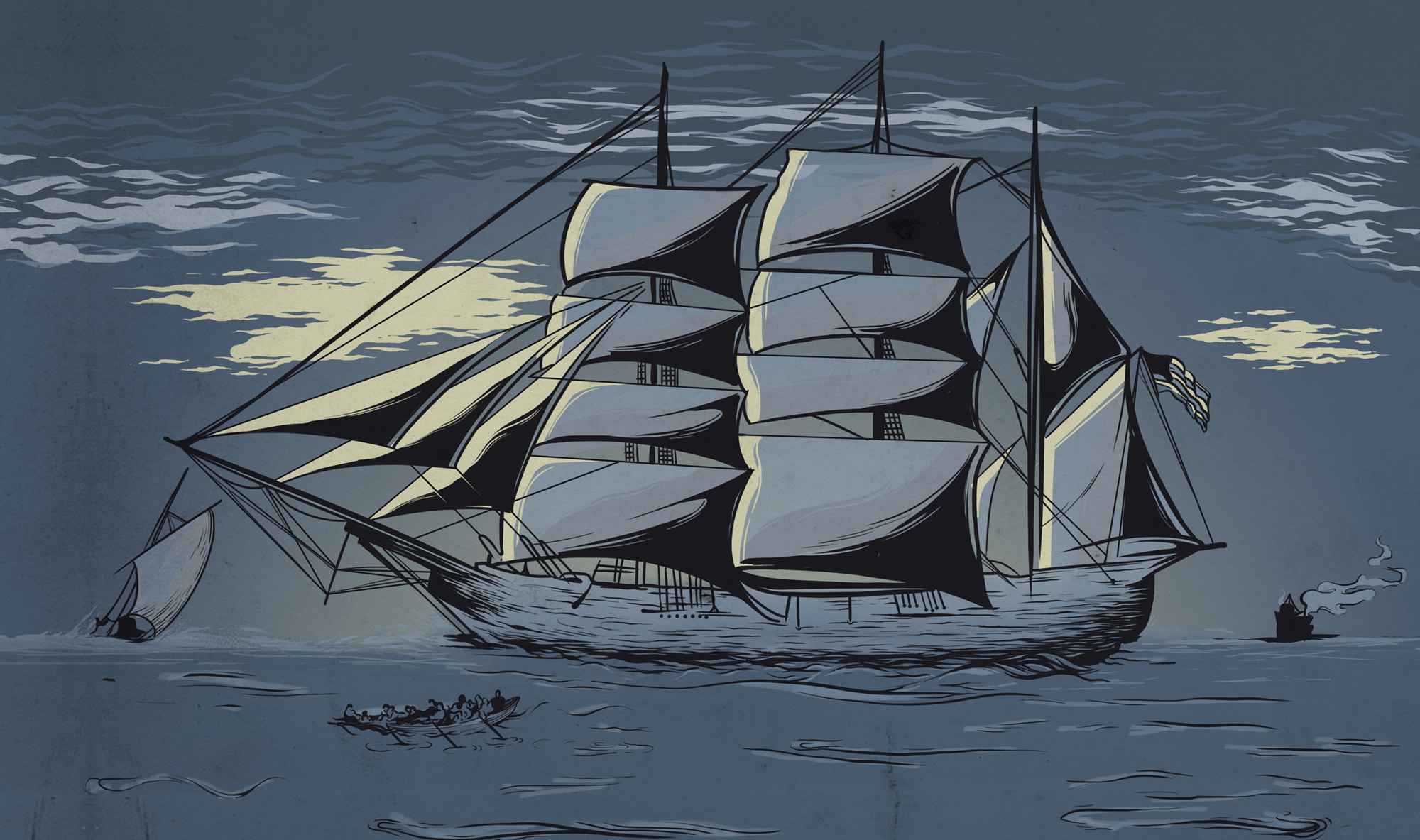

In need of a ship, The Clan purchased the Catalpa – a three masted whaling ship – and crewed her with a mix of loyal agents and ordinary sailors, setting as her Captain an American Quaker named George Smith Anthony. Now, Anthony had no dog in this fight, but he resolved to lend a hand because, as he later said, “it was simply the right thing to do”. That’s as good a reason as any to risk starting a major international incident, if not an actual war. Quakers are pacifists, but they’re not lacking in balls.

The Catalpa sailed to Western Australia from Massachusetts under the pretense of a legitimate voyage. Meanwhile, two Fenian undercover operatives, Tom Desmond and John Breslin, infiltrated the Swan River colony to scope the lay of the land.

On April 17, 1876, the rebels struck from behind the prison’s walls. Wilson and five other Irish captives bolted for the shores of Rockingham in carts supplied by Desmond and Breslin. With the Catalpa anchored in international waters, a ship’s boat was dispatched to pick up the escapees, taking them back to the Catalpa through the heart of a savage storm that lasted until the dawn of the next down and threatened to capsize their tiny vessel. Getting from the shore to the ship took some 28 hours, so remember that the next time you’re complaining about the chop on the Rottnest Ferry.

The conspirators had taken the precaution of cutting the telegraph lines, limiting the amount of power the Crown could bring to bear against them, but Governor Sir William Cleaver Robinson still dispatched two ships in pursuit, with the Fenians reaching the Catalpa just ahead of an armed police cutter. A brief standoff occurred, but came to an end when Captain Anthony, our ridiculously heroic Quaker, pointed out that, since they were an American ship in international waters, any attack on them would be an act of war. Figuring that losing six prisoners was better than losing (another) war with the Americans, the Australian ships disengaged and the Catalpa spent several months dodging Royal Navy forces before sailing into the calm waters of New York harbour on August 19, 1876.

Today a memorial statue stands in Rockingham. Unveiled in 2006, it depicts six wild geese in flight, depicting the six prisoners who flew the coop that day: James Wilson, John Boyle O’Reilly, Thomas Darragh, Robert Cranston, Martin Hogan, and Thomas Hassett.

Illustration by Dipesh ‘Peche’ Prasad